Europe has a treasure trove of 1.8 billion patient records. Yet only 15% of them are actually usable.

It’s not a technological problem. It’s a problem of architecture and governance.

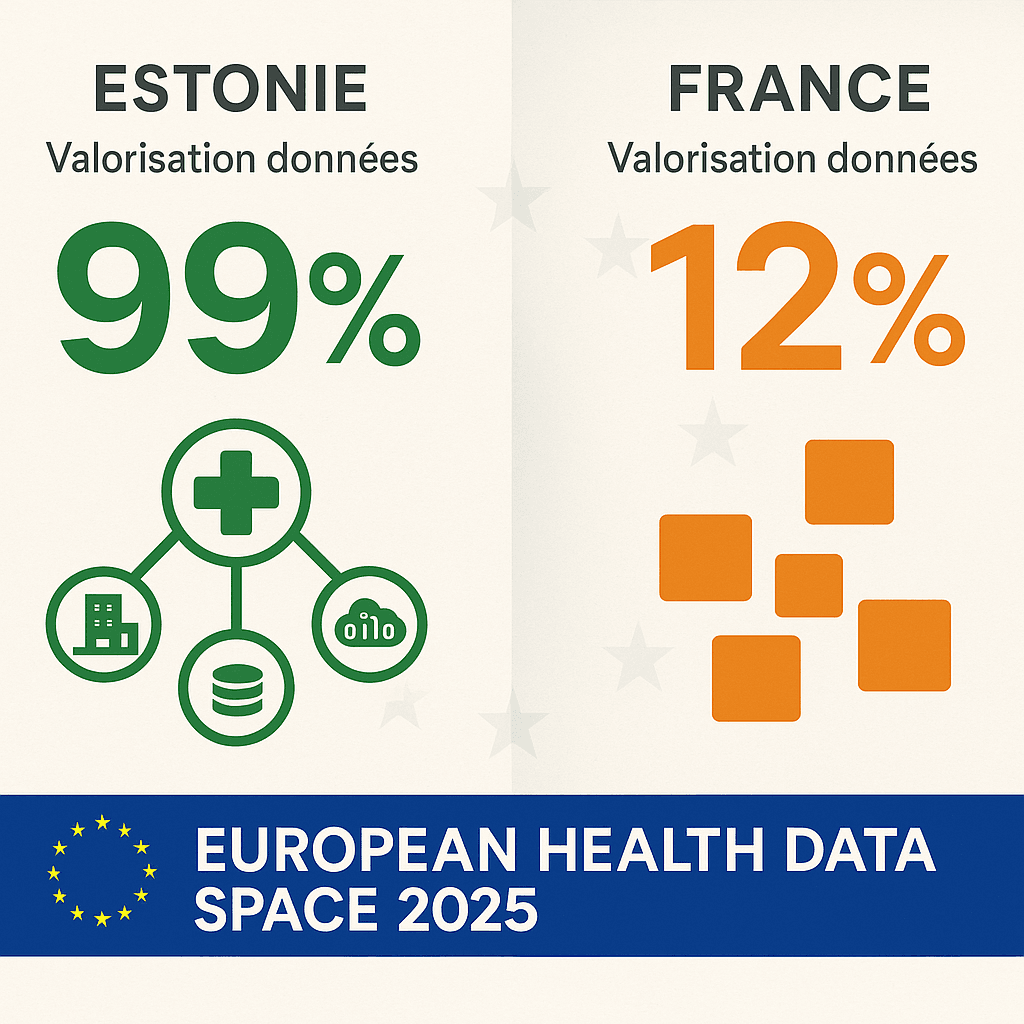

Europe’s digital health transformation reveals a staggering gap. Estonia has 99% of its healthcare data digitized. It also achieves 97% electronic prescriptions. As a result, it has been ranked #1 in the world in e-health since 2024.

Meanwhile, France is stagnating. And yet, it has the National Health Data System (SNDS). What’ s more, this database is one of the richest in the world, with 67 million traced beneficiaries. Despite this, only 12% of the data collected is actually used for secondary re-use in research and innovation.

This difference in valuation, from 1 to 8, does not reflect a difference in budget. Nor does it reflect a lack of technical expertise. In fact, it reveals a fundamental opposition of philosophies. On the one hand, decentralization and public trust. On the other, bureaucratic centralization.

Digital transformation in Europe’s healthcare sector therefore depends on architectural choices. It is also about regulatory choices. Not on investments.

In this article, you’ll discover three key elements. Firstly, the levers that separate Europe’s leaders from the laggards. Secondly, an anonymized case study of a university hospital confronted with this reality. Thirdly, a concrete roadmap for transforming the French gap into an opportunity by 2027.

The European valuation gap: 88% of assets untapped

The figures speak for themselves. By 2024, Estonia had achieved a 99% digitization rate for its healthcare data. Accredited professionals can access data almost immediately. Researchers enjoy the same privilege.

Denmark follows closely behind, with 95% of data usable. Finland reaches 92%. These three countries share a common feature: a decentralized exchange infrastructure. This infrastructure enables interoperability between all players, both public and private.

In contrast, France is stagnating at 12% effective value. Yet this is not for lack of assets. The SNDS aggregates data from the Assurance Maladie. It also centralizes data from public hospitals. It also includes part of the medico-social sector.

Nevertheless, some 800 establishments generate data in heterogeneous formats. France has no functional equivalent to X-Road, the Estonian platform. What’s more, data from private practitioners remains largely absent from the SNDS. This absence creates major blind spots for epidemiological research.

This 88-point gap represents a colossal loss of earnings. An estimate by the European Commission confirms this. Optimal exploitation of healthcare data could generate 144 billion euros by 2030. This value covers clinical research. It also includes the development of personalized therapies. Finally, it concerns the optimization of care paths.

France holds the raw gold. However, it does not know how to industrialize extraction. The 88% of under-utilized data is waiting to be put to good use. They are waiting for administrative barriers to be lifted. They also expect architectural obstacles to disappear.

This situation is about to change radically. When the European Health Data Space (EHDS) regulation comes into force in 2025, the rules will change dramatically. It will impose data re-use by default. It will also impose free access for research and innovation. This regulatory pressure on member states is unprecedented. As a result, France will have no choice but to speed up its digital health transformation. Otherwise, it will face European sanctions. There is also a risk that talent will flee to more fluid ecosystems.

Decentralized architecture vs. centralized silos: two opposing models

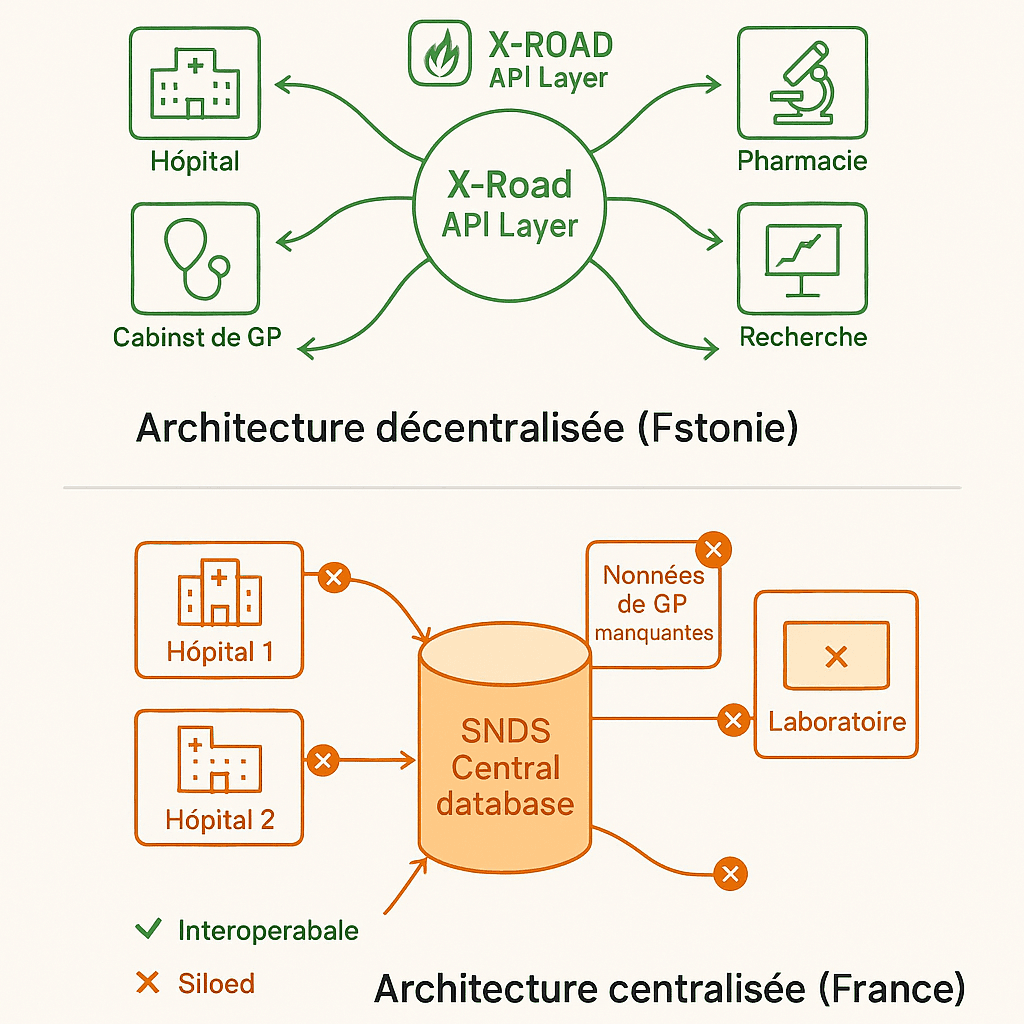

The difference between Estonia and France does not lie in the quantity of data collected. It lies in the architecture that enables their circulation. On the one hand, a decentralized infrastructure favoring interoperability. On the other, centralized silos prevent dynamic access.

The Estonian model: X-Road, the universal exchange layer

The success of Estonia’s digital healthcare transformation relies on X-Road. This critical infrastructure was launched in 2001. It has become the backbone of Estonia’s digital state.

Contrary to popular belief, X-Road is not a single Electronic Patient Record (EPR). The State does not manage a centralized system. In fact, it’s a secure exchange layer. It enables all information systems to interoperate. It connects public and private players. Above all, it does so without centralizing data.

In practical terms, X-Road works like an intelligent router. Each player in the healthcare system retains its data locally. For example, hospitals keep their databases. Similarly, private practitioners control their own systems. And pharmacies remain autonomous. So do laboratories.

However, they all make their data accessible via standardized APIs. These APIs comply with the FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) protocol. So when a general practitioner consults a patient’s file in Tallinn, he can access hospital data in real time. He can also consult laboratory results. He can also view previous prescriptions. But these data have never been duplicated in a central database.

This decentralized architecture offers three major advantages. Firstly, it eliminates aggregation delays. Data is instantly available. It doesn’t pass through a centralized warehouse. They therefore avoid complex ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) processes.

Secondly, it respects data sovereignty. Each player remains the owner of its own systems. They can evolve technologically without waiting. They don’t have to wait for a national update.

Thirdly, it facilitates innovation. Startups and accredited researchers interrogate data via API. They don’t have to negotiate individual access. They don’t have to contact each institution separately. To find out more about the technical standards that make this interoperability possible, read our article on FHIR and open hospital architecture.

The French model: SNDS, a fragmented centralized repository

In France, the SNDS embodies the opposite approach. Created in 2016, it centralizes data from the French health insurance system (SNIIRAM). It also aggregates data from public hospitals (PMSI). It also includes causes of death (CépiDC).

On paper, it’s a gold mine. The system tracks 67 million beneficiaries. Every year, it collects 1.2 billion medical claim forms. Its history goes back to 2006.

Yet, in practice, three structural obstacles drastically limit its exploitation. Firstly, fragmentation persists. The 800 hospital establishments generate data in heterogeneous formats. Some use HL7v2. Others prefer CDA. Some still scan paper. Mass adoption of the FHIR standard remains limited.

Secondly, data from private practitioners is largely lacking. This data is essential for understanding care pathways. Data collection is voluntary. It is based on obsolete billing systems.

Finally, the lack of an equivalent to X-Road poses a problem. Any data query requires manual extraction. CNAM teams have to intervene. This results in incompressible delays.

This bureaucratic centralization is reflected in some damning figures. The median time taken to access SNDS data will reach 10 to 12 months in 2024. In Estonia, this timeframe is only 3 to 6 weeks. What’s more, this French timeframe increased by 56% between 2020 and 2022. Requests were multiplying. Processing capacities were not keeping pace.

To make matters worse, researchers have to pay availability fees. These costs are a major obstacle. SMEs suffer. Innovative startups too.

Interoperability, the cornerstone of digital healthcare transformation

The opposition between these two models reveals a fundamental truth. The digital transformation of healthcare in Europe cannot be measured by the volume of data stored. It is measured by the fluidity of access.

Estonia has chosen to focus on interoperability. It favors open standards (FHIR, HL7). The result is an agile innovation ecosystem.

France favored centralization. It chose control. Now it’s paying the price of paralyzing rigidity.

This architectural difference explains a phenomenon. Estonia now attracts e-health start-ups from all over the world. France, despite its exceptional data assets, is struggling to make the most of them.

Public trust: total transparency vs. administrative opacity

Beyond technical architecture, Europe’s digital healthcare transformation rests on an often overlooked pillar: public trust. Here again, Estonia and France embody two diametrically opposed approaches.

Estonia: blockchain auditability and immediate right of access

Estonia has been using blockchain technology since 2015. It applies the KSI (Keyless Signature Infrastructure) protocol. This protocol guarantees the integrity of healthcare data.

Each access to a patient file generates a cryptographic fingerprint. This fingerprint is time-stamped. It is also immutable. This means that any Estonian citizen can check in real time who is accessing their medical data. They can see when access has taken place, understand why, and simply use the national mobile application. This total transparency transforms administrative surveillance into a permanent citizen audit.

The user experience is exemplary. In two clicks, a patient sees the complete list. They discover which doctors have consulted their files. They can identify the nurses involved. The platform shows him the pharmacists involved. Finally, he or she detects the researchers who have accessed the data.

If access seems illegitimate, he can report it immediately. He contacts the authorities. An automatic investigation is triggered. This traceability is a powerful deterrent. Professionals know it. Any abusive consultation will be detected. It will also be punished.

Result: in 2024, 78% of Estonians had confidence in the national digital healthcare system. In France, this rate is only 34%. This confidence is not a cultural effect. It is the result of institutionalized transparency.

It explains why 97% of Estonians accept the re-use of their data for medical research. They exercise a simple right of opposition. Less than 2% of the population use it.

France: bureaucratic opacity and structural distrust

In France, access to health data is governed by a system of compulsory prior authorization. Any re-use of SNDS data requires the opinion of CESREES. This acronym stands for Comité Éthique et Scientifique pour les Recherches, les Études et les Évaluations dans le domaine de la Santé.

CNIL authorization is also required. This double lock creates a considerable procedural barrier. It is justified by a restrictive reading of the RGPD. To understand this procedure in detail, consult the official CNIL documentation on access to the SNDS.

For a French citizen, finding out who has accessed his or her health data is an obstacle course. They have to submit a written request to the CNIL. They then have to wait between 30 and 60 days, and often receive only partial answers. Sometimes, the answers are too technical.

No consumer application offers the same level of transparency as Estonia. This opacity fuels mistrust. In 2023, only 34% of French people have confidence in the use of their health data for research. What’s more, 41% are completely unaware of the existence of the SNDS.

This mistrust has concrete consequences. French researchers face 10 to 12 months of administrative delays. They also have to justify each request to ethics committees. These committees are often out of touch with the realities of agile innovation.

Meanwhile, their Nordic counterparts launch analyses in a matter of weeks. They publish faster. They attract international funding. To understand how to structure data governance that inspires trust, read our guide to patient data governance and the RGPD.

Towards a European model of trust?

The EHDS imposes transparency as a default principle. It could therefore force France to adopt a model closer to Estonia. The regulation makes explicit provision for this. Every European citizen must have free access to his or her access history. They must have access in real time. They can consult their health data.

This regulatory constraint will create pressure. Competitive pressure between Member States will add to this. These two forces could finally unblock France’s digital healthcare transformation. But this will require a profound cultural change. We need to move from administrative mistrust to trust through transparency.

Anonymized case study: French metropolitan university hospital vs. Tallinn university hospital

To illustrate the gap between these two models, let’s compare two research projects. Both focus on oncology. They were launched simultaneously in January 2024. The first takes place in a French metropolitan university hospital (anonymized). The second takes place at the university hospital in Tallinn, the Estonian capital.

Project A: French university hospital, colorectal cancer recurrence prediction study

A team of French researchers wants to analyze data from 5,000 patients. These patients were treated for colorectal cancer between 2018 and 2023. The aim: to develop a predictive model of recurrence based on artificial intelligence.

The project requires access to SNDS data for care history. It also requires local hospital data. These data include imaging and anatomopathology.

Real timeline :

- January 2024: Creation of CESREES file (3 months)

- April 2024: Favourable opinion CESREES

- May 2024: Submission of CNIL file (4 months of instruction)

- September 2024: CNIL authorization obtained

- October 2024: CNAM contractualization for SNDS access (2 months)

- December 2024: First data set received (11 months after startup)

- Problem detected: Hospital and SNDS data use different patient identifiers. Manual chaining becomes necessary.

- February 2025: Effective start of analysis (13 months after launch)

Total cost: €45,000 (CNAM fees, internal project resources, RGPD legal consultants)

Result: In November 2025, 22 months after launch, the French team published its first results. In the meantime, three international teams had published on similar subjects. Innovation thus becomes less differentiating.

Project B: Tallinn University Hospital, same colorectal cancer study

An Estonian team is launching exactly the same study at exactly the same time. Its aim is identical: to predict colorectal cancer recurrence using AI.

Real timeline :

- January 2024: Application for researcher accreditation to health authority (2 weeks)

- February 2024: Accreditation obtained, X-Road API access activated

- February 2024: Query launched via FHIR API, data extraction 5,000 patients (interoperable standard)

- March 2024: Analysis started (2 months after launch)

- June 2024: AI model developed and clinically validated

- August 2024: International publication (7 months after launch)

Total cost: €8,000 (free API access). However, to structure an AI project in healthcare effectively, methodology is crucial. Our approach <a href=”/implementation-ia-sante-methodologie-agile”>pragmatic AI implementation with JuliaShift framework</a> details these steps.

Result: The Estonian team publishes 15 months before the French team. It attracts 2 million euros in European Horizon 2020 funding. It also licenses its solution to a Scandinavian medtech.

Lessons learned: innovation depends on speed of access

This anonymized case reveals an inconvenient truth. Digital health transformation in Europe is not measured by the scientific quality of the teams. It is measured in terms of administrative and architectural fluidity.

The French team had access to more data. The SNDS covers 67 million beneficiaries. Estonia has only 1.3 million inhabitants. Yet the French team lost 15 months. It also spent €37,000 more. The cause: procedural barriers.

This inefficiency has strategic consequences. Firstly, a brain drain towards more agile ecosystems. Secondly, a loss of attractiveness for international investors. Finally, France is marginalized in European research consortia.

As a result, France’s digital healthcare transformation will not be able to rest on its laurels of incremental optimization. It requires a profound architectural overhaul. It also requires a complete regulatory overhaul.

Transformation roadmap: from EHDS constraints to French opportunities

The entry into force of the European Health Data Space (EHDS) regulation in 2025 will radically change the rules of the game. For the first time, a European regulatory framework will impose a performance obligation on Member States. This obligation concerns interoperability. It also applies to data access.

However, France is structurally lagging behind by 3 to 5 years. This lag is measured against the Nordic and Baltic leaders. How can we transform this constraint into an opportunity between now and 2027?

Short-term (2025): regulatory simplification and one-stop shopping

The immediate priority is to reduce access times to SNDS data. At present, these delays reach 10-12 months. The aim is to bring them down to less than 3 months.

This involves three concrete measures. First, create a digital one-stop shop. This would centralize CESREES and CNIL requests. It would enable parallel rather than sequential processing.

Secondly, revise the CNIL doctrine. Prior authorization should be the exception rather than the rule. This would be based on a system of accreditation for researchers and establishments. This model is inspired by the Estonian system.

Third, introduce free access for academic projects. This free access would be extended to French Tech-certified startups. This would eliminate a discriminatory barrier to entry.

These measures do not require any major technological investment. They are a political decision. We have to accept that digital health transformation is based on trust through accreditation. We can no longer rely on control through prior authorization.

The EHDS requires this evolution. We might as well anticipate it as early as 2025. This would avoid European sanctions in 2026.

Medium-term (2026): architectural revolution and FHIR interoperability

The major strategic challenge lies in the deployment of a French equivalent of X-Road. We could call it “Passerelle Santé”. This decentralized exchange platform would enable interoperability.

It would connect 800 hospitals, 85,000 private practitioners and 21,000 pharmacies. All would interoperate via standardized FHIR APIs. Above all, data would not be centralized in a new warehouse.

In concrete terms, “Passerelle Santé” would function as a software layer. This layer would be added to existing information systems. It would not need to be replaced. Each player would retain local control over his or her data. However, it would make them searchable via APIs compliant with the FHIR R4 standard.

In this way, an accredited researcher could launch a federated query. For example: “all type 2 diabetic patients who received an insulin prescription between 2020 and 2023”. He or she would obtain an aggregated response in a matter of minutes. However, individual data would never leave their source system.

This project is technically feasible. It is also affordable. Denmark has deployed a similar infrastructure (Sundhedsdatanettet). The cost: 80 million euros over 3 years.

On a French scale, a budget of 150 to 200 million euros would suffice. That’s the equivalent of a single medium-sized hospital. The obstacle is not budgetary. It’s political. We have to agree to decentralize data control. In this way, we gain in fluidity of access.

Long-term (2027): public trust and blockchain transparency

Finally, France’s digital healthcare transformation will only be sustainable if it is based on public trust. This means deploying a mobile application for the general public by 2027. This application would enable every French citizen to see in real time who is accessing his or her health data.

A blockchain technology similar to the Estonian KSI would be used. This transparency by design is not a technological gimmick. It meets a democratic requirement. Citizens have the right to control the use of their medical data. This transparency is the sine qua non of social acceptability.

Without it, any use of health data will remain suspect. It will slow down innovation. It will also fuel mistrust. Without this transparency, any use of data will remain suspect. It will slow down innovation. It will also fuel public distrust. Integrating AI into this regulatory context requires special attention. Find out how to implement AI in compliance with the European framework in our article AI Compliance, RGPD and AI Act.

The EHDS explicitly requires this transparency. We might as well integrate it into the design of “Passerelle Santé”. We’d avoid having to add it as a patch later on. The marginal cost is low (a few million euros). On the other hand, the gain in public confidence is considerable.

Europe’s digital health transformation is happening now

The 99% (Estonia) vs. 12% (France) gap reveals an inconvenient truth. Digital health transformation in Europe is not measured by the amount of data held. It is measured by the ability to exploit it.

France has the raw gold. However, it does not know how to industrialize extraction. The 88% of under-exploited data represents a considerable shortfall. This shortfall will amount to 144 billion euros in medical innovation by 2030.

The entry into force of the EHDS in 2025 creates a unique window of opportunity. Member States that anticipate this regulatory constraint will become leaders. They will transform their data architecture. They will also modernize their administrative governance.

Those who wait passively will suffer penalties. They will also see their talents migrate to more fluid ecosystems.

The question is no longer “if” France should transform its model. The question is “when”. And every month of delay widens the gap with our Nordic and Baltic neighbors.

Is your company ready for EHDS 2025, or is it still stuck in CNIL 12-month mode?

Are you a director, CIO or innovation manager in a healthcare establishment?

Aligning with EHDS and simplifying data workflows are essential for innovation and competitiveness. We help you move from data bureaucracy to innovation architecture.

Free 30-minute transformation audit: Diagnosis of administrative and architectural obstacles + identification of “quick wins” 30-90 days to unlock your data and accelerate your research projects.

🎯 Going further

Are you structuring a MedTech fundraiser?

Download our free strategic reports:

- BPI France 50-point compliance checklist

- Timeline 0-6 months pre-emergence

- 3 startup cases (seed → series A)

- Frameworks valorisation multiples Revenue

📥 Download your free reports → Blueprint MedTech

About the author

Nicolas Schneider is a strategic consultant in digital healthcare transformation and founder of JuliaShift. With 17 years’ experience at the Service de Santé des Armées and 8 years in digital transformation consulting, he supports healthcare establishments, MedTech startups and public institutions in adapting to European regulations (EHDS, AI Act, RGPD).

Specialities: FHIR interoperable architecture, AI compliance in healthcare, structuring MedTech fundraising, patient data governance.