March 2025. A case reveals the shortcomings of patient data governance in France. A 68-year-old patient has to be transferred urgently from a university hospital in Lille to Paris. At stake: a critical cardiological expertise. The doctor prints out a 47-page patient file. He slips a USB key with the scan images into an envelope. Six hours later, the Paris cardiologist opens the local DPI. Result: empty.

The USB key? Format incompatible with the receiving CHU imaging system. Paper file? Partially illegible. Consequence: new thoracic scan “for safety”. Complete blood work-up redone. Anamnesis restarted from scratch. In the end: diagnostic delay and costly duplication of tests.

This is not an isolated case. A survey by the Fédération Hospitalière de France (FHF) confirms this. In fact, 25% of inter-hospital transfers require the reproduction of diagnostic tests. The cause: lack of fluid digital exchanges. The estimated national cost is several million euros per year.

Yet the real cost is not financial. It’s human. This problem raises a fundamental question: is patient data governance in France adapted to the reality on the ground? More precisely, who really controls access to and use of healthcare data?

Paradoxically, we’ve been debating for a decade who “owns” health data. The patient? The state? The hospital? Meanwhile, our European neighbors have built operational infrastructures. They have answered a far more pragmatic question: who actually controls access and use?

This semantic distinction is not insignificant. In fact, it reveals a blind spot. Our legal-philosophical obsession prevents us from seeing what’s essential. The real issue is not abstract property. It’s about concrete patient autonomy. It’s also about the efficiency of the healthcare system.

In this article, you’ll discover three key points. Firstly, how the Netherlands solved this problem with the LSP. Second, why My Health Space doesn’t deliver on its promises. Third, a roadmap for building patient data governance based on trust rather than control.

Netherlands: radical transparency as the foundation of trust

Since 2013, the Dutch have deployed the Landelijk Schakelpunt (LSP). This nationwide network connects all healthcare players. GPs, hospitals, pharmacies and emergency services now exchange data seamlessly.

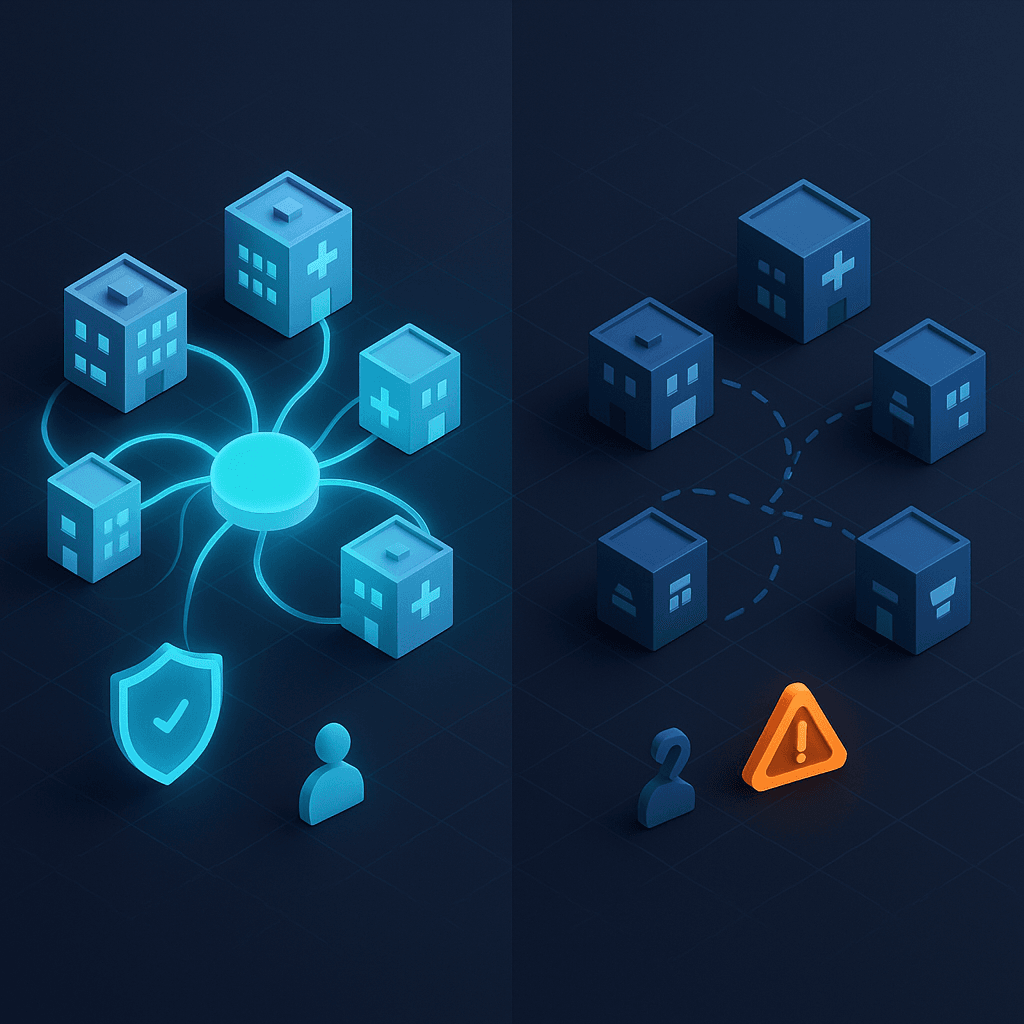

Decentralized architecture: storage remains local

Unlike French attempts at “centralized records”, the LSP does not store any medical data. Instead, the information remains in the healthcare professionals’ own IT systems. In this way, the network functions as a secure directory.

Here’s how it works in practice. A patient arrives at the emergency department. The doctor interrogates the central index with the patient’s social security number (BSN). He then finds out which professionals hold data on the patient. He then accesses their systems directly via encrypted connections.

This approach offers three major advantages. Firstly, there is no risk of hacking into a centralized database. There is no centralized database to hack into. Secondly, each professional retains technical control of his or her systems. Thirdly, technological evolution remains possible without waiting for a national update.

Opt-in consent: explicit activation as the norm

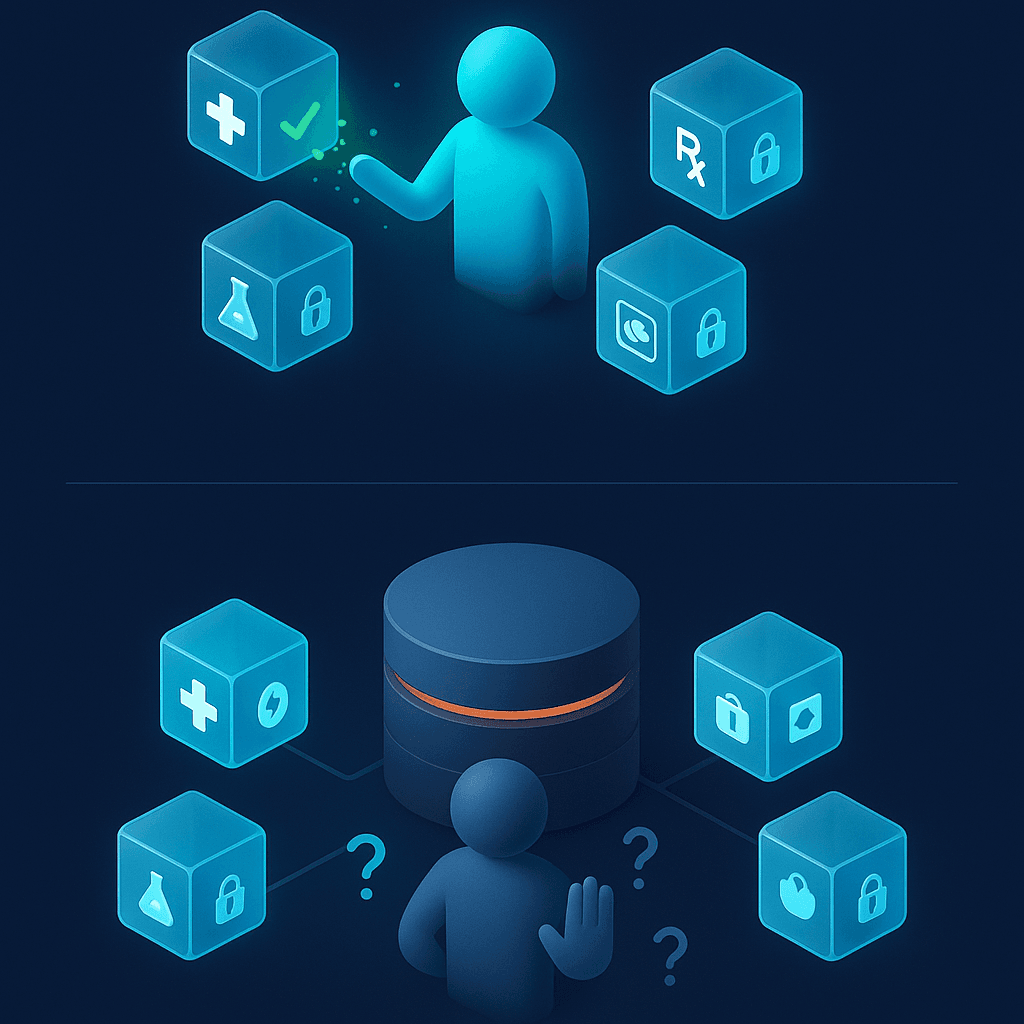

Nothing circulates without the patient’s active consent. However, the real innovation lies elsewhere. Via the Volgjezorg.nl portal, every Dutch citizen can consult in real time who has accessed which data. They can also see when this access took place.

This radical transparency has generated massive trust. The result: millions of users for over a decade. What’ s more, the opposition rate remains below 2% of the population. Why is this? Because citizens have effective control over their data.

The user experience is exemplary. In just three clicks, a patient can view :

- The list of professionals who have accessed your file

- Types of data consulted (prescriptions, imaging, biology)

- The precise dates and times of each access

- The ability to block/unblock access by professional

If an access seems illegitimate, the patient reports it immediately. The authorities then launch an automatic investigation. This traceability is a powerful deterrent. To find out more about the mechanisms of citizen trust in digital transformation, consult our comparative analysis of Digital Transformation in Health Care in Europe.

FHIR migration: modern interoperability as a standard

The system was initially built on HL7 v3. Since then, it has been gradually migrated to FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources). This modern web standard is based on REST API and JSON.

This technical evolution guarantees interoperability with new services. In particular, mobile patient monitoring applications can now be integrated. E-health startups are also developing compatible innovations. As a result, the ecosystem remains open and dynamic.

Measured benefits: efficiency in the service of care

The benefits have been documented for 12 years. Firstly, considerable savings in medical time. Secondly, a drastic reduction in redundant examinations. And finally, improved continuity of care in the emergency department.

But above all, a calmer social consensus on the use of data. The Dutch no longer debate “who owns the data”. They focus on “how to use it for the benefit of the patient”. This collective maturity transforms patient data governance into a competitive advantage.

France: the gap between legal promise and real autonomy

Mon Espace Santé: the flaws of a good intention

France launched Mon Espace Santé in 2022. The system is also based on FHIR. On paper, we have the right technical standards. In practice? A gulf between legal theory and practical autonomy.

Opt-out vs. opt-in: a major philosophical difference

The French system is based on active refusal. By default, the space is created for all insured persons. They must actively oppose its opening. In contrast, the Netherlands has opted for active prior consent.

This philosophical difference changes everything in terms of perceived legitimacy. Indeed, the opt-out creates suspicion. The citizen wonders: “Why did they create my space without asking me?” Opt-in, on the other hand, generates trust. The citizen thinks: “I chose to activate this service for my benefit.”

The figures bear this out. In France, only 34% of citizens have confidence in the use of their health data. In the Netherlands, the figure is 78%. This 44-point difference cannot be explained by culture. It can be explained by the architecture of patient data governance.

No granularity: all or nothing

Mon Espace Santé does not allow any fine-grained control. A mental health patient cannot choose to hide his or her psychiatric diagnosis during a somatic consultation. In practice, everything is visible or nothing is.

However, the Dutch LSP coupled with Volgjezorg offers far greater granularity. The patient can block/unblock access by professional. They can also filter by data type. Finally, he can act in real time.

This French rigidity poses concrete problems. For example, a woman who is a victim of domestic violence cannot hide her address from non-emergency professionals. An HIV+ patient cannot choose to share his or her status only with his or her infectious disease specialist. These limitations violate the very principle of autonomy.

Persistent technical fragmentation

Despite the recommendations of the ANS (Agence du Numérique en Santé) on CI-SIS (Cadre d’Interopérabilité des Systèmes d’Information de Santé), FHIR implementation remains disparate. Each hospital software publisher adapts the profiles in its own way.

The result: islands of compatibility, but no de facto national interoperability. The 800 hospital establishments generate data in heterogeneous formats. Some use HL7v2. Others prefer CDA. Some still scan paper.

This fragmentation explains the case of the patient transferred to Paris from Lille. The systems did not speak the same technical language. And yet, the two university hospitals were officially using “compatible standards”. The gap between theoretical standards and operational reality remains abysmal. To find out how FHIR can solve these interoperability problems, read our detailed article on FHIR and open hospital architecture.

Paradoxical automatic feeding

The DMP (Dossier Médical Partagé, or shared medical file, integrated into Mon Espace Santé) can be fed automatically by professionals. Paradoxically, this feed works even if the patient refuses activation. Data is archived no matter what. The patient must then“activate” his or her space to view them.

This mechanism is legal (decree n°2016-914). However, it perfectly illustrates the gap between “theoretical legal sovereignty” and “real practical autonomy”. Patients do not have effective ownership of their data. They only have a deferred right of access.

In comparison, the Dutch model does not feed any files without prior patient activation. This fundamental difference explains the divergent levels of confidence.

AI in healthcare and data governance: the paradox of sovereignty

We all want sovereign medical artificial intelligence. French algorithms, trained on French data. Able to detect cancer early. Able to optimize care paths. Effective at predicting post-operative complications.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: this AI needs millions of X-rays. It needs scans. And it needs anonymized clinical records to learn.

Confusing anonymization with commercialization

Think of it in concrete terms: your anonymized chest x-rays today train the algorithm. Tomorrow, this algorithm will detect your neighbor’s lung cancer. Your pseudonymized brain MRIs help refine the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. In this way, you contribute to the health of future generations.

Anonymized data ≠ data sold. In reality, it’s a collective investment in our healthcare system. It’s not a commercial transaction. The confusion comes from the fact that some players do indeed have predatory models. In particular, private platforms and assurtech.

However, anonymized sharing for public research uses a radically different logic. So does sharing for therapeutic innovation. Yet this difference is never clearly explained to the public. As a result, mistrust is rife. To find out how to implement AI in this complex regulatory framework, read our guide Compliance AI, RGPD and AI Act.

The Cloud Act and sovereign hypocrisy

We rightly denounce the risks of the American Cloud Act. This text gives the US government access to data stored by American companies. No matter where they are hosted. In fact, the Health Data Hub had to be migrated from Microsoft Azure. The reason: CNIL alerts on international transfers.

But at the same time, AP-HP is deploying chatbots via WhatsApp (Meta, an American company). These deployments raise exactly the same issues of international transfers (RGPD art. 44-50). Yet patients feel protected “because it’s AP-HP”. They are convinced that legal texts are enough.

The gap between ethical display and de facto subcontracting is abysmal. This hypocrisy undermines the credibility of the rhetoric of sovereignty. Worse still, it demonstrates that patient data governance is based on legal appearances. It is not based on auditable technical guarantees.

EHDS: Europe’s opportunity to rethink governance

The European Health Data Space (EHDS) comes into force in March 2025. This regulation will impose cross-border interoperability. FHIR standards will become essential. Health Data Access Bodies (HDABs) will facilitate the secondary use of data for research.

The French Health Data Hub is one of these HDABs. From now on, it will have to comply with common European standards. This regulatory pressure represents a unique opportunity. It could force France to modernize its patient data governance.

The four pillars of trust-based governance

But without a calm collective debate, we run the risk of reproducing our current blockages on a continental scale. The real questions are not philosophical. On the contrary, they are operational.

Pillar 1: Robust, publicly audited anonymization

How can we guarantee that technical anonymization is robust? Above all, how can it be publicly audited? Currently, anonymization algorithms are black boxes. Citizens have to “trust” them. But trust is built on transparency.

Proposal: create an independent certification body. This body would audit anonymization techniques. It would publish accessible reports. This would enable citizens to check that their data is truly protected.

Pillar 2: Economic fair return mechanism

What is the “fair return” mechanism for profits to fund the public system? Diagnostic AI patents generate revenue. Organizational optimizations create value. Yet the public system that provided the data receives no return.

Proposal: introduce a fee proportional to the revenues generated. Manufacturers who exploit the data would pay a contribution. This contribution would finance public infrastructures. It would also support fundamental research.

Pillar 3: Dutch-style transparency adapted to the French context

How do we reconcile Dutch transparency (Volgjezorg) with our French administrative culture? Of course, we have our own cultural specificities. But radical transparency has been working in the Netherlands for 12 years. Why shouldn’t it work in France?

Proposal: develop a transparency portal equivalent to Volgjezorg. Every French citizen would be able to see who is accessing his or her data. They could also control access on a granular basis. Finally, they could revoke authorizations in real time.

Pillar 4: Transparent pricing structure for industrial access

What pricing structure should private industrialists have access to? This scale must be transparent. It must also deter abuse. And it must be sufficient to finance public infrastructures.

Proposal: publish an official price list. Rates would vary according to the type of use. Academic research would pay less. Commercial use would pay more. Above all, all revenues would be publicly tracked.

Sources and references

- CNIL – The Cloud Act and data transfers to the United States: legal framework and recommendations

- HL7 FHIR Standard, Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources, official technical documentation

- European Commission – European Health Data Space (EHDS), regulation and implications for member states

Towards trust-based patient data governance

The failed transfer between Lille and Paris is not a technical inevitability. On the contrary, it’s a political choice of non-priority. As long as we can’t put a figure on the real cost of our fragmentation, we won’t have the arguments we need.

This cost is measured in billions of euros wasted. It is also measured in lost medical hours. Finally, it translates into repeated examinations and avoidable errors.

The Netherlands shows us that a decentralized model can work. A transparent model, too. Above all, a model that respects patient autonomy. This system has been operating nationwide for over a decade. Estonia goes even further with its X-Road model. These systems are not perfect. But they are up and running.

France has the technical skills. We have the research teams, we have the healthcare establishments and we even have the right standards (FHIR via ANS). What are we missing? Social acceptability built on trust.

But trust is built on radical transparency. It is also based on effective control. It’s not based on reassuring legal texts that nobody reads.

Open question: What kind of profit-sharing model between government, citizens and industry do you think would be fair? How can we finally unblock interoperability in France? How can we guarantee responsible innovation?

Are you a CIO, innovation manager or compliance officer in a healthcare establishment?

Patient data governance and EHDS alignment have become major strategic challenges. We can help you structure governance based on trust, technical transparency and regulatory compliance.

Free 30-minute discovery session: Audit of your current governance + identification of RGPD/EHDS risks + 90-day compliance roadmap.

🎯 Going further

Are you structuring a MedTech fundraiser?

Download our free strategic reports:

- BPI France 50-point compliance checklist

- Timeline 0-6 months pre-emergence

- 3 startup cases (seed → series A)

- Frameworks valorisation multiples Revenue

📥 Download your free reports → Blueprint MedTech

About the author

Nicolas Schneider is a strategic consultant in digital healthcare transformation and founder of JuliaShift. With 17 years’ experience at the Service de Santé des Armées and 8 years in digital transformation consulting, he supports healthcare establishments, MedTech startups and public institutions in adapting to European regulations (EHDS, AI Act, RGPD).

Specialities: FHIR interoperable architecture, AI compliance in healthcare, structuring MedTech fundraising, patient data governance.